Canary in the Coal Mine: Long Covid in Fiction

The ongoing pandemic is affecting authors just as it's affecting everyone else. We’re not supposed to talk about it, and we’re treated with disdain if we take precautions to prevent infection. Just the same, authors are not supposed to write about it.

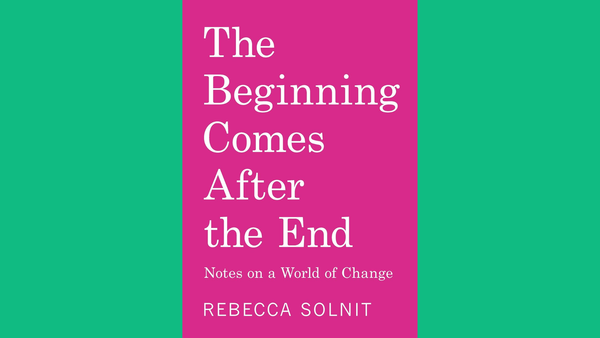

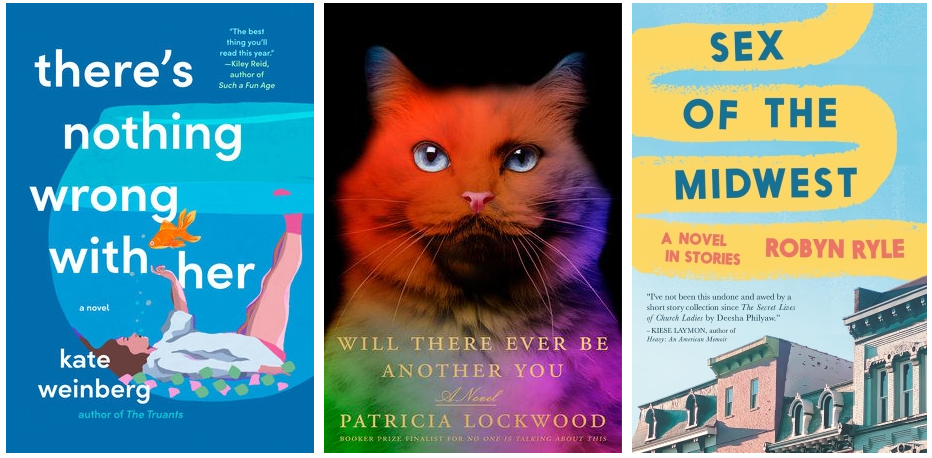

I was anticipating the release of Will There Ever Be Another You (2025) by Patricia Lockwood because I love her work but also because I feel a sense of relief anytime I encounter a discussion of the Covid-19 pandemic in this era of collective forgetting. Lockwood's autofictional novel centers on a writer who is suffering chronic physical and neurological symptoms weeks and months after contracting Covid during the early stages of the global pandemic, as Lockwood did, and as she wrote about in a more straightforward way for July 2020 publication in the London Review of Books.

Recent research suggests that more than one-third of people who contract Covid-19 experience Long Covid. Long Covid is a loose medical term applied to instances where a person has ongoing symptoms for three months or more after infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Covid-19). According to the CDC, a person is more likely to develop Long Covid if they have a particularly severe infection, if they have not been vaccinated against Covid-19, or if they have an underlying health condition. Older people, women, Black people, and Hispanic and Latinx people have also demonstrated a higher likelihood of contracting Long Covid. But it can happen to anyone.

According to a 2023 study by the National Institutes of Health, symptoms of Long Covid can include fatigue, shortness of breath, fever, cognitive impairment (aka “brain fog”), and sleep disturbances, among others. Brain fog is one of the most common symptoms reported, and it is one of the symptoms Lockwood writes about in Will There Ever Be Another You. The participants in the NIH study (most of whom had “mild” symptoms after infection) were found to have dysfunction in their immune and autonomic nervous systems. Other studies have found that many people with Long Covid report trouble with memory, paying attention, intellectual processing, and executive function. Up to 26% report issues with sleep, predominantly insomnia. In many cases Long Covid patients develop mood/mental health issues like depression and anxiety; for those who were already suffering from a mood or mental health disorder, many report a worsening of symptoms.

In the LRB essay, Lockwood writes:

“During a telehealth appointment, I explained to a different blurry doctor that after three months I was still experiencing intermittent symptoms: low-grade fever and difficulty breathing, mysterious arthritic nodules that had developed all over my hands, and for three weeks an almost total numbness in my legs, feet, arms and face. I was aphasic, stumbling in my speech, transposing syllables, choosing the wrong nouns entirely. Some of the delusions I had developed during the most severe phase of illness persisted: that my vision was a picture that had been pasted in front of my eyes, that my floorboards, creaking with the expansive spring humidity, were going to fall through. Hours, days had fallen out of my memory like chunks of plaster.”

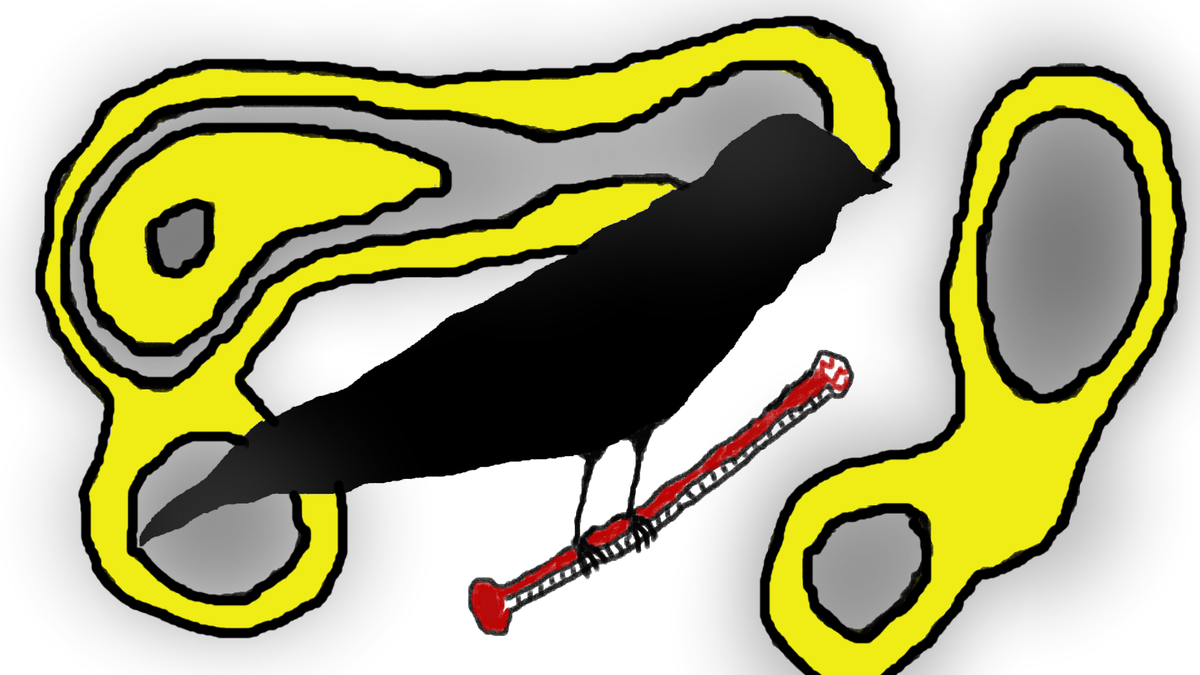

Viruses seek to reproduce, to spread, to continue their existence by means of infection after infection. I have often wondered if the brain fog reported by many as a symptom—both of a single, acute infection and of Long Covid—is an evolutionary preservation tactic for the virus. Those experiencing brain fog and other neurological effects might have difficulty grasping the science of how the virus spreads, or remembering the details. They might develop a sense of apathy about reinfection, assuming that what they are already experiencing is as bad as it could get and feeling too tired and disoriented to do further research, especially when everyone around them is continuing to live like there is nothing to worry about. Research has demonstrated that Covid-19 can affect the brain’s frontal lobe, and possibly even targets it. Scientists have discovered an increase in concussions in high school athletes since the pandemic began (with evidence pointing to a link to Covid infection), an indication that infection could reduce inhibitions and make people more aggressive. Studies have shown not just cognitive difficulties in people with Long Covid, but also problems with emotional regulation. It’s a trope from a zombie apocalypse show—once you are infected you lose the power to protect yourself and others from reinfection.

Lockwood writes of becoming paranoid, believing that her husband, who had also contracted the virus, was faking his cough. She also experienced confusion and memory loss: “One day I realised I couldn’t remember my phone number, another that I couldn’t remember my brother’s middle name. But the most stubborn fact seemed to be that I had forgotten how to read.” For a writer, this is potentially devastating, and Will There Ever Be Another You explores with sensitivity and humor the repercussions of the neurological effects which, fortunately, for Lockwood, did eventually subside.

There’s Nothing Wrong with Her by Kate Weinberg, released in August 2024, has been called the first Long Covid novel. It likewise centers on a protagonist dealing with the condition and, like Will There Ever Be Another You, is based on the author’s personal experience. The character, Vita, is mostly bedbound in her apartment in London, dealing with brain fog, fatigue, and other symptoms. She describes the onset of this illness as a descent into “The Pit.” While it’s heartening to see the subject addressed in fiction at all, the review in The Sick Times points out a number of flaws in the book, including the fact that Vita has a somewhat miraculously fast improvement in symptoms for a condition that has few treatments and is notorious for lasting a long time (for those who are lucky enough not to be permanently affected).

Though she hasn’t incorporated the subject into her work, author Madeline Miller (famous for her retellings of Greek myth, such as The Song of Achilles and Circe) has also spoken publicly about her experience with Long Covid, which bears striking similarity to Lockwood’s. She wrote about it in an article for The Washington Post (republished on Authors Unbound) in 2023. After listing a host of disturbing physical symptoms, she recalls the neurological effects:

“Worst of all, I couldn’t concentrate enough to compose sentences. Writing had been my haven since I was 6. Now, it was my family’s livelihood. I kept looking through my pre-covid novel drafts, desperately trying to prod my sticky, limp brain forward. But I was too tired to answer email, let alone grapple with my book.”

Authors and other public intellectuals think for a living, and their thoughts are a product the rest of us consume. The neurological symptoms of Covid-19 bring the potential for real financial hardship for people like Lockwood, Weinberg, and Miller, and perhaps this is partly why they have been vocal about their experiences. For others, these particular symptoms might be less obvious, less pronounced, easier to ignore or work around. Maybe it’s not very noticeable for those not in the business of selling their thoughts. Maybe the symptoms seem like they can be attributed to some other cause—lack of sleep, aging, stress, etc. But when one of our most interesting and entertaining thinkers tells us she got sick and couldn’t think, couldn’t make sense of words, we should listen to this canary in the coal mine.

In Sex of the Midwest, a “novel in stories” by Robin Ryle published in October 2025, Long Covid is addressed most overtly through the character Don Blankman, a former college basketball coach who contracted the virus in the early stages of the pandemic and is awaiting a lung transplant in 2024, when the novel takes place. But elsewhere, Ryle explores what one might call symbolic or metaphorical Long Covid. For several characters, the pandemic has thrown the events and detritus of their lives, their desires and ambitions and failures, into sharp relief. A bartender named Rachel, for instance, decides on a whim to apply to take part in a writer’s retreat, but when she is there, she feels out of her element, lost and confused. Another character, a child, remarks that they were told by the adults in their life that things would be better after the pandemic was over but that this hasn’t proven to be the case. This is a feeling many can likely relate to, and the reason is that, even though the world has demanded that we believe otherwise, the pandemic isn’t over, and the more we act like this isn’t true, the further we get from an actual ending. The literal experience of Long Covid is also a metaphor for the ongoing trauma and grief we all carry as a result of the pandemic, feelings that can’t be reckoned with honestly or genuinely since we’ve all been left behind by a social and political infrastructure that asks people to put themselves at risk in the name of “moving on.”

In an interview with NPR, Ryle explains:

“I think in a lot of the stories you see - one of the kids who comes back, he talks about, everyone promised us after the pandemic, everything would be better. And he's betrayed by that's not actually true. It's after the pandemic, or at least, you know, the worst of the pandemic, and things aren't really better. So I think part of Rachel and everyone in the story is dealing with this sense that we had this promise if we could just get through, things would be OK. And things didn't turn out the way that maybe we thought they would or people told us they would.”

There are so few books that address Covid-19 that reading something like this feels like hearing someone speak my native language after years and years abroad. I do not have Long Covid; as far as I know I have never contracted Covid-19. (I do have a disabling chronic condition that causes pain and fatigue that would likely be exacerbated exponentially if I got Long Covid.) I wear an N95 mask in all public indoor spaces (and crowded outdoor spaces) at all times and I don’t eat at restaurants. I rarely do other public indoor activities like going to movie theaters. It’s not terribly difficult doing (or not doing) these things, and I feel fortunate to have the resources and support to be able to avoid putting myself and others at risk. What is difficult is watching the rest of the world around me get sick and become disabled while the overall societal message is that nothing is happening. What is difficult is losing relationships with friends and family because I won't compromise on self-preservation or the protection of my community to make them feel okay about the risks they're taking.

Lockwood writes in Will There Ever Be Another You about the fact that the most monumental events of our time are rarely incorporated into our fiction. (She uses the example of 9/11.) She believes this is because “almost as soon as they happened they were transformed into propaganda.” This is true, but it’s not the only reason, and I think the framing could be expanded. While the beginning—what one might call the “lockdown phase”—was certainly a monumental event, the pandemic is not an event at all, it is a historical shift, in which the world has found itself in an entirely new, uncharted dimension. Anyone living their lives like that isn't the case (whether willingly or due to personal, social, or economic pressures), contracting the virus again and again, is in the position of rolling the dice on long-term disability.

There have of course been plenty of other novels about the Covid-19 pandemic—a flurry were released in 2021-2022 in particular—and novels where the pandemic features as backdrop or setting without playing a key role. But we rarely see fiction engaging with the experience of being sick with the virus, or fiction that addresses the reality that the pandemic is still the setting in which we’re all living our lives. Lockwood has commented on the fact that her publisher expressed serious reservations about the content of her book. In both Will There Ever Be Another You and There’s Nothing Wrong with Her, Covid is rarely mentioned by name. A review of Lockwood’s book in The Sick Times quotes a researcher studying Covid-19 in literature: “Owing to the sheer despair of our current world and the want to move on from the pandemic, this type of writing lacks marketability.” No kidding. And it’s worth noting that the three books discussed in this article were all written by white women, two of whom were already relatively well-known with active publishing contracts. One can easily imagine how difficult getting such a book published might be for Black or Latinx people, who, again, are disproportionately affected by Long Covid. Also, the fact that marginalized populations are more likely to deal with Long Covid cannot be separated from its lack of supposed "marketability."

The ongoing pandemic is affecting authors just as it's affecting everyone else. We’re not supposed to talk about it, and we’re treated with disdain if we take precautions to prevent infection. Just the same, authors are not supposed to write about it. We see the tension in this emerging, as fiction writers quite commonly draw from their real lives, and thus this would seem a natural subject. If up to one-third of people who contract Covid-19 also acquire some form of Long Covid, this is something quite a lot of authors are dealing with. Maybe Lockwood’s and Weinberg’s novels represent the beginning of a shift in how the condition appears in literature. While one might criticize either book as being an imperfect representation of Long Covid, both evince a kind of wild and vulnerable bravery in approaching this subject at all.

Will There Ever Be Another You is a vivid and arresting portrait of a mind in rapid decline, that is so entertaining partly because we know the end of this true story is not a tragedy. For many others with Long Covid there is no such restorative arc. Most authors who contract the disabling condition won’t write an exceptional book about it—because of what Lockwood says about it being taboo subject matter, because the world so obviously has little desire to hear about how Covid-19 continues to affect people, or because their cognition is so dramatically affected they can no longer do the work required to shape their story into something the rest of us can read. Instead there will just be silence, a gap where a great book could have been.

Who Even Reads is an independent publication run by two hardworking editorial professionals. We write about books from a liberation perspective, with a socially conscious focus that's both fun and serious, covering mostly new releases. Your donations subsidize what we do. Learn about us.